"Goodbye to Berlin": Connection Through the Ages

A chance pickup at a bookstore opened up a deep and intimate world to which I was previously entirely unaware.

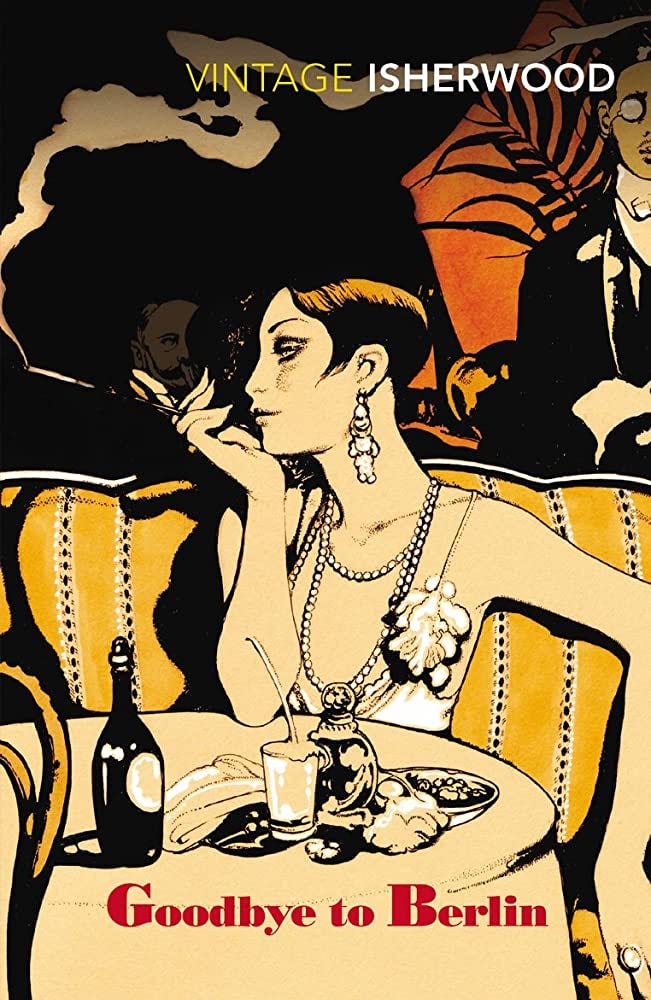

I spotted Goodbye to Berlin on the Germany table at Daunt Books in London. Daunt Books is one of the most fabulous bookstores I’ve been to, and although I have a penchant for used bookstores, the perfectly new, shiny covers that line the walls and cover the tables at Daunt are equally as enticing as the dog-eared copies one finds at Powell’s. Daunt bills itself as a bookstore for travelers, even if the only traveling one is doing is within the pages of a brilliant novel.

Goodbye to Berlin by Christopher Isherwood is one of those novels.

I’ve only transited through Germany, and although I have a trip planned to Munich in September, this book has ignited something within me that longs to see the difference between the past and present in Berlin.

I was originally enticed by the beautiful cover of the book. The title is equally as interesting and when I flipped it around and saw the endorsement from George Orwell and the seemingly modern book blurb, I was sold. I bought it immediately, but waited to begin it until I got home from my trip.

I am particularly picky about when to begin a book or spin a record or watch a movie. I believe, however misguided it may be in reality, that there’s always a right time to read, listen, or watch something. Some things come at the exact right moment in life; for example, I read the first few sentences of Jay Parini’s introduction to This Side of Paradise by F. Scott Fitzgerald just before I was about to turn 19, and Parini said he read it for the first time at the exact same age. I immediately stopped reading the introduction at that point, wanting to be fresh as I read the novel. I don’t think I ever made it back. Sorry, Jay.

I picked the exact right time to read Goodbye to Berlin. I think that I saw it in Daunt for a reason. I had heard of Isherwood before, as I had already had one of his other books, Prater Violet, on my Goodreads “Want to Read” list for a year or so. Yet, it had been difficult for me to obtain a copy of it, so another one of his novels seemed like a good place to start instead.

I’ve already mentioned how I’m at a curious point in my life right now. I’m fairly certain I’m the only person in my university of 21,000 undergraduates to be studying abroad for the whole year. After that, I’ve got an uncertain summer, likely to be spent abroad, then one last victory lap at USC before I head off abroad again for school or work. I’m at a nebulous point of existence, hovering somewhere between the here and now and the not-so-distant future. It’s compounded by that future taking place 6,000 miles away.

Yet, Goodbye to Berlin felt familiar in the most distant way. It was a picture — more like multiple snapshots — of a society so far removed from my own, yet distinctly familiar. People are people, no matter if they lived 10, 100, or 1,000 years ago. The mannerisms of Isherwood’s characters were so relatable that I could find comparisons for them in my own life. Frl. Schroeder could be the sweet, if slightly overbearing house mom of my friend’s sorority, while Natalie Landauer could be any of the girls at my school. The characters seem as if picked directly from real life and dropped into the novel, and although it is indeed true that Isherwood based the book on his own life experiences, it also speaks to his mastery of writing that all of them seem so realistic.

I was hesitant at first when I began the book, for Isherwood’s style is particularly brash. He isn’t shy about using racial descriptors or rather crass language to describe the people the narrator encounters — and while that is something that should be rightfully criticized at times — I accepted it as part of his style and the era within which he was writing, and I looked beyond my initial distasteful impression. Then, I began to see the beauty of Isherwood’s prose. At first glance, it appears simple, but as you delve deeper into the novel and into Isherwood’s Berlin, it becomes complex and paints a tragicomic portrait of a society balanced on a knife’s edge while trying to maintain a semblance of normalcy. Isherwood’s characters are not the sanitized versions of people that may come to mind when we think of the 1930s; for sometimes it feels as if every era before our own was full of nuns and censorship (I always think of Ricky and Lucy’s separate beds).

In Isherwood’s Berlin, however, each character and scene springs to life with all the gory details of reality. Sections of town are overflowing with weeds and grime, while the narrator and Fritz Wendel visit the nastiest, low down clubs and hangouts of Berlin. The book is covered in poverty, contrasted especially well with the wealth of the narrator’s various students. On every single page, Isherwood maintains a positive attitude — and a dear love for Berlin — but the crushing reality of the time is also made clear. Most of the novel’s characters live in poverty, including everyone else’s favorite, Sally Bowles. I liked Sally’s character well enough, but I found other characters more interesting, such as the aforementioned Frl. Schroeder and Bernhard Landauer.

Isherwood’s genius lays in the fact that every single scene in the novel is enjoyable. Not once did I get bored; instead, it felt like I was an unnoticed but not unwanted voyeur upon the small intricacies, boredoms, joys, and tragedies of every day life in Weimar Berlin. This is a period of history that I am extremely unfamiliar with, and such a personal, intimate account of it, obviously painstakingly written with love and adoration of this confusing, sad time was heart wrenching in the best way. I am a firm believer that reading opens one’s mind and creates empathy, and the bridge I felt between myself and the varied cast of characters in Isherwood’s Berlin was immense.

The book feels like not only a goodbye to Berlin in the sense that Isherwood was forced to leave when Hitler took power, but also that it was an emotional farewell to a city that Isherwood loved and that loved him right back. Goodbye to Berlin was one of the best books I’ve read because it affected me in a way I didn’t expect. I often find myself reading books that appear on “Top 100 Books to Read Before You Die” lists or maybe even a book that your 10th grade English teacher would beg you to read on their hands and knees, and since I’ve heard so much about these books already, it was refreshing to read a great old book that I knew nothing about. With books like The Great Gatsby or Frankenstein (two of my favorites!), their fame precedes them. Yes, they are amazing, with wonderful prose and insightful commentary, but you can already recite the plot before you even sit down with them for the first time. With Goodbye to Berlin, I had an unexpected peek into a period of history so familiar and yet so alien to my own. It encouraged me to contemplate my own biases, and much like the class on Fascism I took in freshman year of college, it opened my eyes to the complexities of living under such an oppressive regime constantly nipping at one’s heels. Anxiety lingers behind every corner in Goodbye to Berlin, and when certain snippets of the primary sources we read in my Fascism class sprung to mind or the narrator described small scenes of Nazi fanaticism, shivers went down my spine. The book is a diligent record of a time filled with equal parts normalcy and terror. I appreciated Isherwood’s honesty and attention to detail on every page.

I’ll leave you with the finals sentences of Goodbye to Berlin. After spending over 250 pages with Isherwood’s Berlin, they were particularly chilling. I encourage you to seek this book out and experience it for yourself.

“I catch sight of my face in the mirror of a shop, and am horrified to see that I am smiling. You can’t help smiling, in such beautiful weather. The trams are going up and down the Kleiststrasse, just as usual. They, and the people on the pavement, and the tea-cosy dome of the Nollendorfplatz station have an air of curious familiarity, of striking resemblance to something one remembers as normal and pleasant in the past — like a very good photography.

No. Even now I can’t altogether believe that any of this has really happened…”

Vive in perpetuum,

Hannah Contreras